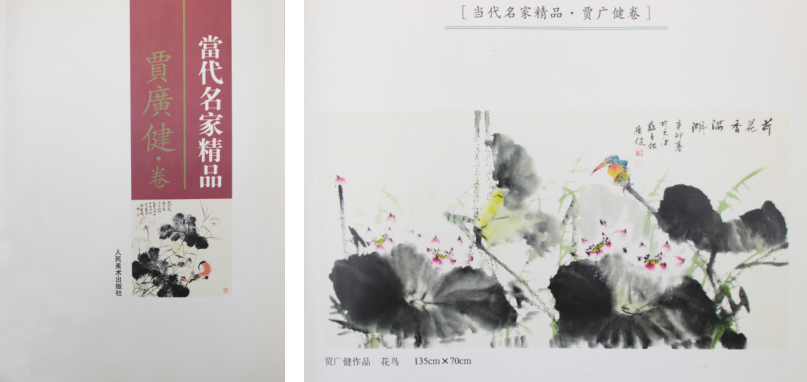

Premium Recommendation -Flowers and Birds by Jia Guangjian

*本次藏品:贾广健《花鸟》*

典藏尺寸:重:3.3g直径:25.5mm

(此画已收录于当代名家精品画卷,并附有画册)

这幅画属于贾广健典型的 “大景花鸟” 构图,虽未采用其早期工笔荷花的巨幅形制,却以横向舒展的小写意没骨法,突破了传统 “折枝花鸟” 的局促。画面创作于 2011 年(辛卯年),此时的贾广健已从天津美术学院中国画系副主任、硕士生导师的身份,转向中国国家画院教授的创作与研究,艺术风格正处于 “工笔向写意温和过渡” 的成熟期 —— 既保留了工笔阶段对物象细节的精准把握,又融入了写意笔墨的挥洒与气韵。

从署款 “天津 藕香馆” 可知,这幅作品是贾广健在天津创作的系列荷塘题材之一。作为土生土长的河北永清人,贾广健对北方荷塘的晨昏变化、花叶姿态有着深入的写生积累:“我常蹲在荷塘边看,荷叶在不同光线下的绿是不一样的,晨露时是润的,正午是亮的,傍晚是沉的”。而 2011 年的创作,恰好处于他 “以色彩为背景、以没骨为语言” 的探索期,这幅作品中 “淡赭铺底、墨色氤氲” 的处理,正是其 “形色分离” 色彩理念的实践。

贾广健的荷花作品,最鲜明的特质是 “以没骨为体,以写意为魂”。这幅画的笔墨语言,集中体现了他对传统技法的 “守正创新”。

没骨画源于北宋徐崇嗣,盛于清代恽南田,核心是 “不用墨线勾勒,全以色彩点染”。贾广健在这幅作品中,并未完全恪守传统没骨的 “淡彩轻施”,而是融入了水墨写意的 “浓淡干湿”:

荷叶以 “泼墨 + 破墨” 写成:大片墨色铺陈后,以清水破出边缘的 “气感”,墨色从焦黑、浓灰到淡青自然过渡,既保留了荷叶的厚重质感,又通过水分控制营造出 “水气淋漓” 的朦胧感;

荷花则以 “淡粉晕染 + 细笔提点” 完成:花瓣边缘用极淡的胭脂色分层晕染,花蕊处以鹅黄、赭石点出细节,既避免了工笔的刻板,又比纯粹的写意更显 “娇嫩鲜活”。

这种处理,恰如他所言:“没骨不是无骨,是‘骨藏于肉’—— 用色彩的层次代替线条的勾勒,让形与色融成一体”。

传统花鸟画以线条为骨,而贾广健在此作中弱化了 “线” 的存在感,却又在不经意处透出笔力:

荷梗以 “中锋淡墨” 写出,线条细劲却暗含弹性,如同宋代院体画的 “高古游丝描”,虽不刻意强调,却支撑起画面的纵向结构;

翠鸟的轮廓以 “焦墨短线” 勾勒,喙部、眼部的细节用 “钉头鼠尾描” 提点,与荷花的 “隐线” 形成对比,让主体形象在朦胧的荷塘中 “脱颖而出”。

这种 “线藏于墨色、骨隐于气韵” 的手法,正是他 “工写融合” 的典型特征 —— 看似写意,实则处处有工笔的严谨;看似没骨,实则笔笔有法度的支撑。

贾广健深谙 “墨分五色” 的传统,却又赋予其现代的层次意识:

画面中的墨色从 “焦墨(荷叶阴影)”“浓墨(荷叶主体)”“重墨(背景)”“淡墨(荷叶边缘)” 到 “清墨(水痕)”,形成丰富的渐变;

墨色与色彩并非 “墨主色辅”,而是 “色墨互渗”:荷叶的墨色中晕入淡绿,荷花的粉色中融入淡墨,让色与墨 “你中有我,我中有你”,既保留了国画的 “墨韵”,又增强了视觉的 “鲜活感”。

This painting adopts Jia Guangjian's typical "large-scale flower-and-bird" composition. Though it abandons the massive format of his early fine-brush lotus works, it breaks the confinement of traditional "flower-branch painting" through the horizontally stretched freehand boneless technique. Created in 2011 (the year of Xinmao in the Chinese zodiac), this piece coincides with a pivotal period in Jia's career: he transitioned from serving as the Deputy Director and Master’s Supervisor of the Chinese Painting Department at Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts to taking up the role of Professor at the China National Academy of Painting. During this mature phase of artistic evolution, his style was undergoing a gentle shift from fine-brush painting to freehand brushwork—retaining the precise grasp of object details honed in his fine-brush period while integrating the free-spirited verve of freehand brushwork.

The signature "Ouxiang Studio, Tianjin" reveals that this work is part of a series of lotus pond-themed paintings created by Jia Guangjian in Tianjin. A native of Yongqing, Hebei Province, Jia has accumulated profound observational sketches of the changing hues and postures of northern lotus ponds from dawn to dusk: "I often squat by the lotus pond to observe—the green of the lotus leaves varies with light: moist at dawn with dew, bright at noon, and deep at dusk." The year 2011 also marked his experimental phase of "using color as the background and boneless technique as the expressive language". The painting’s treatment of "light ochre underpainting and misty ink wash" stands as a concrete practice of his color theory of "separation of form and color".

A defining characteristic of Jia Guangjian’s lotus paintings is "taking boneless technique as the form and freehand spirit as the essence". The brush and ink language of this piece epitomizes his philosophy of "upholding tradition while pursuing innovation" toward conventional techniques.

The boneless painting technique originated with Xu Chongsi in the Northern Song Dynasty and flourished in the Qing Dynasty under Yun Nantian. Its core principle lies in "depicting forms through color washes entirely, without relying on ink outlines". In this work, Jia Guangjian does not rigidly adhere to the traditional boneless approach of "subtle light color application"; instead, he incorporates the freehand ink wash elements of "variations in density, dryness and wetness":

The lotus leaves are rendered using the "splashed ink + broken ink" method: after laying down broad swathes of ink, clear water is applied to create a sense of "airy transparency" along the edges. The ink transitions seamlessly from intense black to thick gray and pale cyan, preserving the lush texture of the leaves while using water control to evoke a misty, "damp and fluid" atmosphere.

The lotus flowers are completed with "light pink washes + delicate detail strokes": the petal edges are layered with extremely pale carmine washes, and the stamens are accentuated with touches of goose yellow and ochre. This approach avoids the stiffness of fine-brush painting while imbuing the flowers with a vivid tenderness lacking in pure freehand brushwork.

As Jia himself put it: "Boneless painting is not truly without 'bones'—rather, the 'bones lie hidden within the flesh'—using color gradations to replace ink outlines, merging form and color into an organic whole."

Traditional flower-and-bird paintings rely on lines as the "bones" of the composition. In this work, Jia Guangjian downplays the prominence of lines yet subtly conveys the strength of his brushwork:

The lotus stems are painted with "central-tip light ink strokes"—slender yet resilient, reminiscent of the elegant "ancient gossamer line" of the Song Dynasty academy paintings. Though understated, these lines anchor the vertical structure of the entire composition.

The outline of the kingfisher is defined with "short, intense ink strokes", and details of its beak and eyes are added using the "nail-head rat-tail line" technique. This creates a striking contrast with the "hidden lines" of the lotus flowers, making the bird stand out vividly against the misty lotus pond backdrop.

This technique of "lines concealed within ink washes, bones hidden within artistic verve" exemplifies Jia’s signature integration of fine-brush and freehand styles—appearing free-spirited at first glance, yet underpinned by the rigor of fine-brush painting; seemingly boneless, yet every stroke follows established artistic principles.

Jia Guangjian possesses a profound mastery of the traditional concept of "five gradations of ink", yet he infuses it with a modern sense of layered structure:

The ink tones in the painting range from "charred ink (lotus leaf shadows)", "thick ink (main lotus leaf forms)", "heavy ink (background)", "light ink (lotus leaf edges)" to "clear ink (water marks)", creating a rich, nuanced gradient.

Instead of the traditional hierarchy of "ink as primary, color as secondary", Jia achieves a harmonious "interpenetration of ink and color": pale green blends into the ink of the lotus leaves, and light ink merges with the pink of the flowers. This mutual infusion preserves the poetic charm of traditional Chinese ink painting while enhancing the visual vitality of the composition.

*本次藏品:贾广健《花鸟》*

典藏尺寸:重:3.3g直径:25.5mm

(此画已收录于当代名家精品画卷,并附有画册)

这幅画的构图,体现了贾广健 “突破折枝、全景造境” 的创作理念 —— 他打破了传统花鸟画 “以小见大” 的小品式构图,以 “满幅铺陈却疏密有致” 的方式,构建出一个 “生机盎然的荷塘生态”。

1. 全景式的 “大景花鸟”

传统折枝花鸟仅取一花一叶,而贾广健在此作中展现了 “荷塘一角” 的完整生态:

前景是 “仰观” 的荷叶,墨色浓重,占据画面下半部分,营造出 “近景的厚重”;

中景是盛放的荷花、待放的花苞,色彩明亮,成为视觉的焦点;

背景是 “俯观” 的荷叶、淡墨的水草,墨色轻淡,延伸出 “远景的开阔”。

这种 “近 – 中 – 远” 的层次,虽未采用西方的焦点透视,却通过 “墨色浓淡、物象大小” 的对比,营造出 “深远的空间感”,恰如他所说:“我把花鸟放回自然里,不是画一朵花,是画一整个世界”。

2. 意象的 “符号性” 与 “精神性”

画面中的每一个元素,都不仅是自然物象的再现,更是文化与精神的隐喻:

荷花:选取 “盛放” 与 “初绽” 的形态,少见残荷,这是贾广健的刻意选择 ——“荷是生生不息的象征,我画的不是花,是生命的饱满与向上”。而 “出淤泥而不染” 的文化意象,在此作中通过 “洁净的色彩、朦胧的水气” 得到强化,成为 “清雅人格” 的象征;

翠鸟:立于荷梗之上,姿态警觉却眼神温和,与荷塘的静谧形成 “动与静” 的对比。贾广健常以翠鸟、鸳鸯等水禽入画,“它们是荷塘的‘灵’—— 让静态的花叶有了生命的互动,也让画面有了‘活气’”;

水气:画面中无处不在的 “淡墨水痕”,既是荷塘的自然特征,更是 “清气” 的视觉化表达。贾广健说:“清是一种气,是画面里飘着的东西 —— 让观者看画时,仿佛能闻到荷香,感受到塘边的风”。

3. 虚实与疏密的辩证

这幅作品看似 “满幅铺陈”,实则处处有 “虚实的留白”:

实:荷花、翠鸟、前景荷叶是 “实”,墨色浓重、细节清晰;

虚:背景的水草、荷叶边缘的水痕是 “虚”,墨色轻淡、形态朦胧;

疏:荷梗之间、花瓣之间留有空隙,让气韵得以流动;

密:荷叶的重叠、花叶的交错形成 “密”,让画面显得 “饱满丰厚”。

这种 “满而不塞、密而不挤” 的处理,正是中国传统美学 “虚实相生” 的体现 —— 看似画满了荷塘,实则留给观者 “想象的空间”,让满塘的荷花延伸出 “香满湖” 的意境。

贾广健的荷花作品,从来不是 “对自然的复制”,而是 “对生命与文化的提炼”。这幅《荷花香满湖》的深层意蕴,可从三个维度解读:

对传统人文精神的当代诠释

荷花在中国文化中是 “高洁” 的象征,从周敦颐的《爱莲说》到文人画中的 “荷意象”,早已成为一种文化基因。贾广健在此作中,并未直接 “图解” 这种文化符号,而是通过 “笔墨的清雅、形态的饱满”,让荷的 “高洁” 从 “概念” 转化为 “可感的视觉体验”:

画面中没有尘俗的元素,只有荷、叶、鸟、水,构建出一个 “脱离尘嚣的净界”;

色彩的淡雅、墨色的温润,传递出 “平和、宁静” 的心境,恰是传统文人 “守拙归真” 的精神追求。

正如他所说:“画荷不是画花,是画一种生活态度 —— 在浮躁的世界里,留一片清净给自己”。

对自然生命的敬畏与礼赞

贾广健强调 “万物有灵,万物有情”,他的荷花作品始终充满 “生命的温度”:

这幅作品中的荷花,花瓣舒展、花蕊饱满,仿佛能感受到其 “生长的力量”;

翠鸟的姿态放松,与荷塘融为一体,体现了 “人与自然的和谐”。

这种 “生命感”,源于他长期的写生积累:“我在荷塘边看一朵花从绽放到盛开,看一只鸟从飞起落到栖息,这些细节不是画出来的,是‘养’出来的 —— 把自己放进自然里,才能感受到生命的真”。

对 “心象” 的诗意表达

贾广健的荷花,是 “心象” 而非 “物象”—— 他将现实的荷塘转化为 “心灵的荷塘”:

画面中的 “水气” 并非真实的水,而是 “心境的朦胧”;

荷花的 “清雅” 并非自然的颜色,而是 “心灵的洁净”。

这种 “以心造境” 的方式,正是中国传统美学 “外师造化,中得心源” 的当代实践。正如他在《墨有心香》展览中所言:“我的画是‘心香’—— 用笔墨烧一炷香,敬自然,敬生命,敬心中的那片清净”。

贾广健的《荷花香满湖》,是一幅 “可观、可感、可品” 的作品:观其形,是满塘荷花的生机盎然;感其气,是清雅洁净的心灵触动;品其味,是传统与现代、自然与心灵的交融。

这幅创作于辛卯春的作品,如同贾广健艺术生涯的一个 “切片”—— 它浓缩了他对传统技法的传承、对自然生命的敬畏、对文化精神的坚守。正如他自己所说:“我画荷,是画自己的心境 —— 希望每一个看画的人,都能在这满塘清气里,找到自己的那瓣心香”。

The composition of this painting embodies Jia Guangjian’s artistic philosophy of "breaking free from flower-branch conventions and constructing panoramic realms". He abandons the small-scale, "seeing the big picture through the small" composition of traditional flower-and-bird paintings, and instead creates a "vibrant lotus pond ecosystem" through a dense yet well-proportioned full-frame arrangement.

Panoramic "Large-Scale Flower-and-Bird" Composition

Traditional flower-branch paintings only depict a single flower or leaf, but in this work, Jia Guangjian presents a complete ecosystem of "a corner of the lotus pond":

The foreground features upward-looking lotus leaves rendered in heavy ink, occupying the lower half of the painting and creating a sense of "near-field solidity".

The middle ground showcases blooming lotus flowers and unopened buds in bright colors, serving as the visual focal point.

The background consists of downward-looking lotus leaves and light-ink water plants, extending to evoke a sense of "far-field spaciousness".

This foreground-middle ground-background layering does not adopt Western linear perspective; instead, it creates a profound sense of spatial depth through the contrast of "ink density and object scale". As Jia himself stated: "I place flowers and birds back into nature—not painting a single flower, but an entire world."

Symbolism and Spirituality of Images

Every element in the painting is not merely a reproduction of natural objects, but a metaphor for culture and spirit:

Lotus Flowers: The deliberate choice of fully bloomed and newly opened flowers, with few withered ones, reflects Jia’s artistic intention: "The lotus is a symbol of perpetual vitality. What I paint is not just flowers, but the fullness and upward momentum of life." The cultural connotation of "growing unstained from mud" is reinforced through "pure colors and misty moisture" in this work, making the lotus a symbol of "elegant integrity".

Kingfisher: Perched on a lotus stem, it strikes an alert yet gentle posture, creating a dynamic-static contrast with the tranquility of the pond. Jia often incorporates waterfowl such as kingfishers and mandarin ducks into his paintings: "They are the 'soul' of the lotus pond—infusing static flowers and leaves with lively interaction and breathing vitality into the entire composition."

Moisture: The ubiquitous "light-ink water marks" are not only a natural feature of the lotus pond but also a visual manifestation of "pure aura". Jia explained: "Purity is a kind of energy, something that lingers in the painting—allowing viewers to seemingly smell the lotus fragrance and feel the breeze by the pond as they gaze at it."

Dialectics of Emptiness and Fullness, Density and Spaciousness

Though the painting appears to be "fully filled with details", it contains subtle "empty spaces of negative form" everywhere:

Solid Elements: The lotus flowers, kingfisher, and foreground lotus leaves are rendered in dense ink with clear details, representing the "solid".

Empty Elements: The background water plants and water marks along the leaf edges are painted in light ink with blurred forms, embodying the "empty".

Spacious Areas: Gaps between lotus stems and petals allow the artistic energy to flow freely, creating a sense of "spaciousness".

Dense Areas: Overlapping lotus leaves and interwoven flowers and foliage form areas of "density", lending the painting a rich and substantial feel.

This treatment of "full yet not congested, dense yet not cramped" embodies the traditional Chinese aesthetic principle of "mutual generation of emptiness and solidity". While the composition is filled with lotus pond imagery, it leaves ample room for viewers’ imagination, extending the artistic conception from "a pond of lotus" to "fragrance filling the entire lake".

Jia Guangjian’s lotus paintings are never mere "copies of nature", but rather "distillations of life and culture". The profound implication of Lotus Fragrance Filling the Lake can be interpreted from three dimensions:

1. Contemporary Interpretation of Traditional Humanistic Spirit

The lotus has long been a symbol of "nobility and purity" in Chinese culture. From Zhou Dunyi’s Ode to the Lotus to the "lotus imagery" in literati paintings, it has become an integral part of cultural heritage. In this work, Jia Guangjian does not directly "illustrate" this cultural symbol; instead, he transforms the lotus’s "nobility" from an abstract concept into a tangible visual experience through "elegant brushwork and plump forms":

Free from mundane elements, the painting only features lotus flowers, leaves, birds, and water, constructing a "pure realm detached from worldly hustle".

The soft color palette and gentle ink tones convey a state of "peace and tranquility", echoing the traditional literati’s spiritual pursuit of "embracing simplicity and returning to nature".

As Jia noted: "Painting lotus is not just painting flowers—it is painting an attitude toward life: in a restless world, reserve a corner of purity for oneself."

2. Reverence and Praise for Natural Life

Jia emphasizes that "all things possess spirit and emotion", and his lotus paintings are always infused with "the warmth of life":

The lotus flowers in this work boast stretched petals and full stamens, exuding a palpable sense of "growth and vitality".

The relaxed posture of the kingfisher, integrated harmoniously with the pond, reflects the "harmony between humans and nature".

This "sense of life" stems from his long-term observational sketching: "I watch a flower bloom from bud to full blossom, and a bird fly and perch by the pond. These details are not painted—they are nurtured. Only by immersing oneself in nature can one truly feel the essence of life."

3. Poetic Expression of "Mental Images"

Jia Guangjian’s lotus paintings are "mental images" rather than mere "physical objects"—he transforms the real lotus pond into a "spiritual lotus pond":

The "moisture" in the painting is not actual water, but the "haze of inner tranquility".

The "elegance and purity" of the lotus flowers are not just natural colors, but the "clarity of the soul".

This approach of "creating realms through the mind" is a contemporary practice of the traditional Chinese aesthetic principle of "learning from nature outwardly, and drawing from the heart inwardly". As Jia stated in his exhibition Fragrance of the Heart in Ink: "My paintings are 'heart fragrance'—using brush and ink to light a stick of incense, paying homage to nature, to life, and to the purity cherished in my heart."

Lotus Fragrance Filling the Lake is a work that can be viewed, felt, and savored: viewing it reveals the vibrant vitality of a pond full of lotus; feeling it stirs the soul with a sense of elegance and purity; savoring it appreciates the integration of tradition and modernity, nature and spirit.

Created in the spring of the Xinmao Year (2011), this painting is like a "slice" of Jia Guangjian’s artistic career—it encapsulates his inheritance of traditional techniques, reverence for natural life, and commitment to cultural spirit. As he put it himself: "When I paint lotus, I paint my inner state of mind—I hope every viewer can find their own 'heart fragrance' within the pure aura of this lotus pond."

*本次藏品:贾广健《花鸟》*

典藏尺寸:重:3.3g直径:25.5mm

(此画已收录于当代名家精品画卷,并附有画册)

以上藏品相关信息请与:四川尚亿拍卖有限公司联系。

For information about the above collections, please contact: Sichuan Jun Zailai Auction Group Co.